The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Fauré Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

Gabriel Fauré

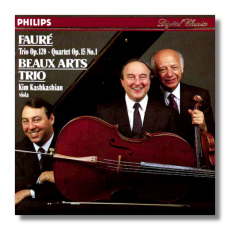

Piano Quartet & Trio

- Piano Quartet #1 in C minor, Op. 15

- Piano Trio in D minor, Op. 120

Kim Kashkashian, viola

Beaux Arts Trio

Philips 422350-2

Unfortunately, if we judge by concert programs, the chamber music repertoire comes down, not only to a few composers, but a few pieces. Mozart, Beethoven, and Brahms receive great attention, but I can't recall the last time I heard a Schubert work live other than the Cello Quintet, the "Trout" Quintet, or the "Death and the Maiden" string quartet. I have never attended a concert and heard a Dvořák quartet other than the "American," although his works for keyboard and strings don't suffer from neglect. I've never heard a Haydn piano trio live (he wrote over 40, most of them brilliant). I've awaited a Mendelssohn revival for years (to me, his most interesting stuff – other than "Elijah" – is his chamber work), and you might as well forget non-German composers, Dvořák excepted, altogether. From necessity, I've had to limit my exploration of chamber music to recordings – not, I contend, the best way to confront it. More than any other genre, chamber music for me requires the immediate presence of the performers. Composers can be Olympian (hence, remote) in their orchestral works, but in chamber music they talk to us face to face. Ideally, I want to play it and thus become part of that conversation.

Of the nineteenth-century French before Debussy, Fauré towers over his colleagues, even Saint-Saëns and Franck, at least as a chamber composer. In fact, he's the only one of them the equal of Brahms. I find only one misfire in his output, the String Quartet – the last in the catalogue and, I suspect, unfinished. On the other hand, to me Brahms' string quartets pale next to every other chamber piece he wrote, and he lacked the excuse of death. Fauré and Brahms share an ease among complexity, the ability to construct forms which satisfy a listener, and a high seriousness of purpose.

Brahms, of course, caught the last from Beethoven's music, especially the middle and late periods, and from Schumann. In comparison, Fauré in many ways comes off as a sport of nature. He has no similar tradition to build on. Further, his harmonic sense is just about unique to him. It's chromatic, but not like Wagner, Brahms, or Bruckner. It's modally and enharmonically flavored, like Debussy, but still within the constraints of traditional harmonic hierarchy, which Debussy very quickly renounces. In Fauré, we get no chords from Mars, but we fly way up in the stratosphere, nevertheless. I regard Fauré as one of the most elusive composers. There's no out-and-out orchestral hit. His best and most characteristic work tends to be song and chamber music. I've counted only one moment in his entire output (the Requiem; the amazing chord shift in the Agnus Dei at "Lux aeterna" that opens up heaven) that I might remotely accuse of glitz. There's an emotional lid on the music. We await both the storm and the bounding spring, but they happen off-stage, so to speak. We see a smooth surface, constantly shifting color, under which an ocean roils.

In the first Piano Quartet, the Beaux Arts emphasize the refined workmanship and the smooth surface. They play elegantly and consequently make the mistake of reducing the music to pastels. Fauré becomes the epitome of French Good Taste, but this is only part of him. There's a wild Romantic streak in him as well, and the conflict – the attempt to repress or tame the latter, if you wish – produces the music's emotional sparks. The first and last movements especially seem anemic. Beaux Arts does best in the Scherzo, where Pressler flicks off diamonds, and where the lighter tone suits the music. Still, I prefer the "no-name" ensemble in a Vox two-fer (CDX5073) which programs both piano quartets and both piano quintets. The Vox musicians play rougher, and the pianist doesn't begin to approach Pressler as a shaper of performance, but to them, the music points to something beyond polite conversation.

The Piano Trio, one of the last works of the composer, fares so much better, I find it difficult to believe that the Beaux Arts fell so short in the conceptually easier Piano Quartet. In the Trio, fewer instruments allow the lines to become more independent, which destabilizes the harmony even further. In a sense, there are more "holes" through which the underlying unease can escape. This crowns Fauré's chamber music – a work of great depth and, with the composer cocking his snoot at old age, great vitality. The gorgeous slow movement to me is the quintessence of Fauré, not only in its expressive content, but in its method of construction. Brahms, for example, builds something very sturdy, but mainly he extends earlier principles. It's a bit like looking at a Tudor mansion, wired with fiber optic. Fauré is a bit eccentric as a builder. The house is just as sturdy, but you keep suddenly coming across rooms you've never seen before. I haven't done this, but I'm reasonably sure that if I analyzed the work, I'd find all the pieces of classical form. The proportions of the pieces, however, are pretty weird. For one thing, it's almost impossible to figure out a priori which theme will bear the major interest of a movement. I suspect much of this idiosyncrasy due to Fauré's experience as a composer of songs (one of the very greatest), where in large part the text determines the structure. Here, the Trio's slow movement takes you on a ramble. One thing leads to another, but when you look back, where you've ended up surprises you: you have little idea how you got there. Again, the Beaux Arts (Menahem Pressler, piano; Isidore Cohen, violin; Peter Wiley, cello) captures the almost other-worldly beauty of this piece.

The sound is Philips and quite fine.

Copyright © 1996, Steve Schwartz