The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

American Piano Music

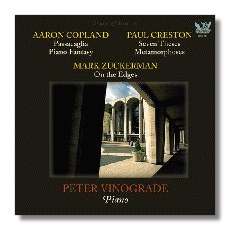

- Aaron Copland:

- Passacaglia

- Piano Fantasy

- Paul Creston:

- Metamorphoses

- Mark Zuckerman:

- On the Edges

Peter Vinograde, piano

Phoenix USA PHCD149 74:31

Summary for the Busy Executive: Terrific explorations of terrae incognitae.

I've praised Peter Vinograde's playing and musicianship before when I reviewed a CD of music by Nicolas Flagello (Albany 234). Here, he tackles two acknowledged masterpieces, both by Copland, and three unknown works. I'll tackle the Creston and Zuckerman first.

Creston's Seven Theses will probably shock those who know items like the marimba concertino or the Symphony #2. The work lies far closer, at least in its harmonic thought, to American Modernism (say, Copland's music of the Twenties) than to what we might expect from familiar Creston - diatonic chords leavened with major sevenths and ninths. The work - a series of short mood studies - stems from 1933, and it shows Creston in the process of finding his composing self. It's apparently a more conscious act than people realize. The muse may descend, but she tends to do so to people who are already working their behinds off. It will take Creston a few years to hit on his characteristic sound, but he does hit it.

Metamorphoses, a variation set, comes from the early Sixties, after Creston's music had begun to sink into oblivion. Part of it was the times. Young composers had once again symbolically killed their musical fathers to pursue mainly Webern's brand of serialism. Creston was by no means alone: a lot of wonderful music got crammed into a dark, forgotten corner of the closet, along with the 16mm family films. Composers like Creston were caught between a rock and a hard place. Their music was anathema to the zealots on both sides of the aisle - the terminally traditional and the terminally cool. If anyone was going to do Creston, it was going to be the new-music crowd, but those guys were essentially distracted by bright shiny objects. In Metamorphoses, Creston writes one of his most structurally ambitious pieces. He plays the game of variations as composers since Beethoven have. One aims to produce not merely telling individual variations, but a satisfying whole built from the variations. Think of something like Elgar's Enigma s. Creston puts several barriers in his way, including a highly chromatic theme (in which every note of the chromatic scale sounds at least twice) of listener-taxing length. He may have gotten the idea from the dodecaphonists, though he doesn't write serially or atonally. In my opinion, he doesn't clear the barriers. The basic theme doesn't interest me in itself, although it's distinctive enough that one can remember its general shape, and while I admire individual variations and discern his strategy for building the entire work, the whole doesn't do much for me, despite some interesting moments. I keep waiting for it to catch fire, which it does, but in fits and starts. The ending, however, is wonderful - beautifully conceived and sustained.

Most of all, the piece interests me as a window on Creston's late period. This and the Choreografic Suite are the most recent Creston works I've heard, and the man had twenty years of composing to go, dying in the Eighties. Metamorphoses shows Creston moving on from his familiar sound in the Forties and early Fifties to something more rugged and edgy. I'd love to know how the story turns out.

Mark Zuckerman is younger than I am by a couple of years. Theoretically, he should be writing serially. He studied with Babbitt at Princeton, and indeed his early works reflect this. He had a career in the academy. A funny thing, however, happened along the way. Unhappy in the academy and facing something of a creative block, he left. He began to split his music into tonal (serially influenced) and serial (classically influenced). Just by listening, I suspect that On the Edges is one of the serials. However, it is considerably helped by strong, exciting rhythm and by ties to classical procedures. In short, it doesn't sound like Everyone's Cliché Serial Piece, although here and there one runs into some well-worn "melodic" turns. Most of all, it impresses as a whole. The joys of musical architecture aren't everybody's cup of tea, but for me that's the joy of the work. I especially admire the basic idea turned into a four-part invention.

The Coplands, however, are the big news on the disc. They come from early and late - the Boulanger and serial periods of his career. When I think of characteristic Copland, I find myself remembering enchanting chords, exquisitely spaced - the opening to Appalachian Spring or the Clarinet Concerto, for example. These two piano works, however, made me realize how much Copland's music depends on a vigorous two-part counterpoint. One would expect this in something like the early Passacaglia, a contrapuntal Baroque form in which a set of variations occurs over a repeating bass. Copland follows the models. However, his is one of the few passacaglias I've heard not in triple meter. It's taut, neat, and eager to say important things. It's a promise that Copland kept.

The Piano Fantasy counts as one of the monuments in Copland's catalogue - for my money, the finest piano piece he wrote. Copland's music tends to divide into "easy" and "hard." The Fantasy definitely falls into the "hard" camp. It took him, I believe, five or six years to write. It was, in his words, "a very hard nut." He originally conceived it as a concerto for William Kapell, a musician he greatly admired. By the time he finished, Kapell had died in a plane crash, the piece had lost the orchestra, and it was a year late for the scheduled première. One reason why was Copland's determination not to repeat himself or echo anybody else. The première at Juilliard (the commissioning body) was probably Copland's most prestigious. The Fantasy was the only thing on the program, and it was played twice, with an intermission between each instance. The audience was a Who's Who of musical New York (although première pianist William Masselos's recollection of Arnold Schoenberg in the audience - in 1957! - comes from either a bad case of nerves or wishful thinking). Copland got a dream review from Howard Taubman in the New York Times.

A half-hour of music entirely free of cliché and determined to create its own set of conventions makes things tough on executant and listener. Part of the ease of assimilating music comes from its resemblance to what we've already heard. Works like the Piano Fantasy resemble really only themselves rather than other things. Even Copland's use of serialism differs from orthodoxy. He uses a series of ten notes, rather than twelve, and keeps the extra two notes for, in his words, "special occasions." His view of serialism anticipates much of what goes on today in new tonal music:

To describe a composer as a twelve-toner, I felt, was much too vague. The Piano Fantasy is by no means rigorously controlled twelve-tone music, but it makes liberal use of devices associated with that technique. It seemed to me at the time that the twelve-tone method was pointing in two opposite directions: toward the extreme ideal of total organization with electronic applications, and toward a gradual absorption into what had become a very freely interpreted tonalism. My use of the method in the Piano Fantasy was of the latter kind.

Far more difficult than making sense of the language, in my opinion, is grasping the form. The Fantasy sounds free and rhapsodic, but in fact the composer has a very tight grip. For me as listener, I find that I've got to follow it as I'd follow, say, Ives' Concord Sonata: keep a tight grip from the beginning on the narrative and don't let go. It's not a work you find programmed or recorded a lot, although it has attracted many superb pianists. I've heard Masselos and Smit, as well as Vinograde. Of the three, I prefer Vinograde. He seems to have the most "natural" view of the work, although such an interpretation probably arises from a lot of grunt time.

In fact, Vinograde does superbly with all these works. The Zuckerman and the Creston are no days at the beach either. Vinograde burns down the barn with all of them. He is one exciting pianist who nevertheless has the ability to convey the overall "story" of these works. I wonder what his Beethoven is like.

Liner notes are by Walter Simmons, a champion of American music. The recorded sound is fine.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz