The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Ginastera Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

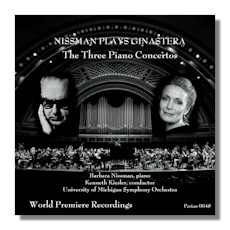

Alberto Ginastera

The Three Piano Concertos

- Concierto Argentino *

- Concerto for Piano #1, Op. 28

- Concerto for Piano #2, Op. 39 (Original version) *

Barbara Nissman, piano

University of Michigan Symphony Orchestra/Kenneth Kiesler

* First Recordings

Pierian Recording Society 48

Summary for the Busy Executive: Recording milestones.

Once again, Pierian has come up with an historically and artistically significant release. Alberto Ginastera, arguably the finest composer Latin America produced, is represented by, if you can believe it, two premieres of major works in powerful performances by Barbara Nissman, one of the great postwar pianists, whose knowledge of Ginastera's music runs deep and who championed the composer for decades. She became a Ginastera family friend. Ginastera wrote his Third Piano Sonata especially for her.

After his death, she discovered the manuscript of an early piano concerto – known about, but withdrawn by the composer almost immediately – in a Philadelphia library collection. We owe the concerto's existence to Nicholas Slonimsky, who in a tour of South America had brought back scores he found interesting. Ginastera, a self-critic ruthless just short of creative stasis, removed most of his early work from public hearing, preferring to begin his Op. 1 with the ballet Panambi of 1937. However, he had been writing hard since at least 1934 and even after Panambi dropped several works down the oubliette. Furthermore, shortly before his death, he softened toward the concerto and planned a revision, but he never got to it.

Ginastera wrote his Concierto Argentino at the astonishing age of 19. Listening to it for the first time, I couldn't help but ask why he withdrew such an attractive work. It may lack the tightness of mature Ginastera, but it does show that he had the knack of reaching a listener from very early on. With certain composers – Byrd, Beethoven, Stravinsky, Gershwin, Mahler, Copland, Poulenc, Bartók, and, yes, Ginastera, among others – each phrase seems to carry a boatload of meaning in a musical narrative that continuously compels listener attention. Among us all, the roster of such composers probably differs. I love Schoenberg and Brahms, but I seem to listen at a certain remove. Ginastera, on the other hand, gives me an immediate jump. I get it in this concerto. I suppose composers aren't always the best judges of their own work. They constantly measure the distance between what they aim to do and what they achieve. Listeners usually don't receive the piece in such a way, mainly because they don't know or even feel the shape or, consequently, the necessity of the ideal.

In some ways, the concerto reminds me of the Gershwin concerto. That is, much of its effect depends on the quality of its singing. It begins with what could be a harsh Bartókian riff, but quickly becomes a dance – I think an early Ginastera take on the malambo – and then a long, lyrical singing. Indeed, this idea, varied as a dance or as a song turns out to be the basis of the entire movement. The piano writing shows a great understanding of the virtuoso possibilities of the instrument. The absolutely gorgeous orchestration foreshadows many masterpieces down the road.

The slow movement breathes nocturnal calm as well as, like many Ginastera slow movements, a bit of lonely. The finale, another malambo, seems inspired, according to Nissman's informative liner notes, by the out-of-tune playing of street bands, and takes a surprising turn into a theme that becomes the finale to the ballet Estancia, at least five years ahead. To my ears, the orchestration also points to the Variaciones Concertantes. In all, like Gershwin's Cuban Overture, the concerto makes a strong appeal to listeners, capturing Latin rhythms and melody in a very Thirties way, on the border of pop, although with tremendous craft. It should survive, if enough performers and conductors take it up. In the meantime, I strongly urge you to beat the crowd.

The official First Piano Concerto a quarter of a century later made a huge splash. Premiered on recording by the breathtaking Brazilian pianist João Carlos Martins and Erich Leinsdorf leading the Boston, the concerto sent Ginastera's international career into the stratosphere. For me, a musical flat-earther at the time, it was an epiphany when I heard a live broadcast in the mid-Sixties. I thought serialism an artistic dead end, limited in expression. Ginastera showed me there was no such thing as a bad method, although there was certainly a ton of unimaginative composers. Furthermore, a good composer didn't stop being himself simply because of the method of composition. Ginastera serial possessed all the virtues of Ginastera tonal. If you can handle Bartók's First Piano Concerto, you shouldn't have trouble with Ginastera's.

The work has four movements: dramatic opening, scherzo, slow movement, and fast conclusion. The opening bars let you know immediately what sort of concerto this will be – a volcanic Lisztian powerhouse with juxtaposition of extremes in tempo, dynamics, and character. Piano is not only the equal of the orchestra, but it occasionally dominates. As I've hinted, this is a serial piece, but in the fifty years I've listened to it, I have no idea of the basic cell, mainly because I don't need to know. The drama grips me tightly and brings me along. The second movement begins with the sounds of exotic birds and muffled beasts. To me, Ginastera has extended Bartók's "night music" – muted scampering which occasionally roars and then retreats back into the deep shadows. The slow movement, hushed and intense, seems an extended prelude to the riotous finale – what I've called elsewhere a "brood and explode" rhetoric – a toccata heavy on percussion. Ginastera takes the pounding almost to the point of intolerance. However, his mastery of musical narrative basically gets you roiling, backs off a bit to let you catch your breath, and then hits you again. This movement actually became a mild hit in a pop arrangement by Keith Emerson of Emerson, Lake, and Palmer. It bears about the same relationship to Ginastera's concerto as "A Fifth of Beethoven" does to the Fifth Symphony. But the impulse to make the arrangement and its commercial reception don't surprise me. Ginastera has the power to reach a wide public, just as Copland and Vaughan Williams do. Despite the magnificent craft, a streak of vulgarity saves him from the genteel.

The Second Concerto has had less luck. It stands in roughly the same relationship to its predecessor as the Brahms Second Concerto does to his First. Although filled with great things, it dials back a bit on the Sturm und Drang, in favor of a more Classical ideal. A committed Ginastera fan by this time (1972), the new concerto left me cold when I first heard it. After several years of listening (not all at once, naturally), I gave it up as a misfire. Of course, I knew it in the only available recording: commissioning soloist Hilde Somer. Her playing never did do much for me. It also turns out that she disfigured Ginastera's score with her own improvements, going so far as to add her own measures to the finale and to rewrite the second movement. The composer had intended it for right hand alone. For reasons known only to her, Somer transcribed it for the left hand alone. Nissman's is the very first recording to present what the composer actually wrote. In other words, up to this point, Ginastera wasn't allowed to fail on his own. Somer gave him plenty of help.

The new concerto also has four movements mostly of the same character as their counterparts in the First Concerto. The first, titled "32 Variazioni sopra un accordo di Beethoven," pays explicit and implicit homage to Beethoven. Beethoven, of course, created several masterly variation sets, including (although overshadowed by the Diabellis) the 32 Variations in c. Unusually, Ginastera's variations do not stem from a theme, but from a distinctive 7-note chord from the finale of the Ninth Symphony (at the passage beginning "Brüder! Über Sternenzelt") – a daring conception. Ginastera adds five more notes to get his 12-note row. This time, you can figure it out more easily than in the first, but once again, you needn't follow its compositional manipulations for the piece to work on you, any more than you need to be able to harmonically analyze Beethoven's Ninth. The sound of the Beethoven chord sticks so hard in the memory, you may even recognize it instantly, and that sound or some variation of it stays with you throughout the movement. I haven't yet gotten to the point where I can pick out each of the 32 variations, but Ginastera does provide strong, dramatic contrasts as well as a wide range of expression. The orchestration runs to the brilliant and original as well as to massive sonorities (although these, interestingly, come from the soloist, more often than not) and chamber-like delicacy. Furthermore, Nissman's very informative liner notes point out some of the major signposts, including a variation which quotes the opening of the "Lebewohl" piano sonata. The movement ends on the sonority and the row, varied.

The scherzo for right hand alone is also a toccata which makes almost no attempt to suggest (as Ravel does in his left-hand concerto) more than one hand, although Ginastera hasn't made things easy for the player, who leaps from one end of the keyboard to the other and almost never gets a respite from hard-edged sounds. At the end, the pianist makes a super-near-glissando from the murky depths to dissipate in the ozone layer.

The adagio movement, "Quasi una fantasia," begins with a long orchestral crescendo, essentially repeated by a solo passage for the piano. However, the lid definitely stays on, thus ratcheting up expectations for some sort of outburst, which again comes from the finale, titled "Cadenza." This time, we don't get a driving toccata right out of the gate, but great upheavals ("Maestoso drammatico") before a presto finale is set loose. Also, instead of a dance ultimately derivable from the folk malambo, we get something more abstract, but just as exciting. Ginastera knows how to wind his listeners up. A magnificent work, the concerto should appeal to mavens and "just folks" alike. Of course, as with any other piece, each listener has to be willing to surrender to it. In this case, the score, the work of a master artisan, provides a huge emotional payoff from somewhat abstract means.

The piano writing for both concerti, heroic and virtuosic, requires a powerful player. The Concierto Argentino is an exciting new discovery. Unabashedly aiming for popularity, it's as if we now have a new Tchaikovsky First or Grieg. Martins killed in his recording of the first, but I've heard plenty of tamer pianists or ones who seemed overwhelmed. I never thought anyone would better Martins. Nissman, however, certainly equals him, although in her own way. Where Martins seemed to wrench the music from or to land blows on the score, Nissman's account grows from the score. She has plenty of power and drama, but she also has a tighter grip on the music's flow. Somer's account of the second (and, I'm sorry to say, every other account of the second) drop from consideration because they use an inferior, corrupt text. Nissman has first place almost by default, but this ignores her deep understanding of a super-complex work. Nissman has always impressed me, not only with her intellect and her adult sensibility, but with her full-blooded playing. She always gives you a challenging (but never bizarre) new take on almost everything she touches. I'd love to hear her do the Brahms and the Rachmaninoff concerti. Orchestras and conductors, please take note. The University of Michigan Orchestra consists of students, so it's not fair to compare them to the likes of the Boston or Vienna Symphonies. Ginastera uses knife-sharp rhythms, and the orchestra doesn't always synch. But both Nissman and conductor Kiesler keep them enough together, so that they don't significantly detract. They have the heart, if not always the cells, of the score.

So you have three strong reasons for buying this CD: a joyful discovery, a powerful classic, and strong championing of an essentially new masterpiece, all in masterly performances.

Copyright © 2013, Steve Schwartz