The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Dvořák Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

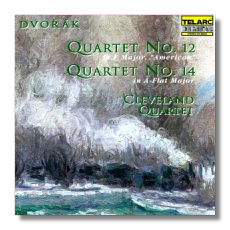

Antonín Dvořák

String Quartets

- String Quartet #14 in A Flat Major, Op. 105

- String Quartet #12 in F Major, Op. 96 "American"

Cleveland Quartet (Preucil, Salaff, Dunham, Katz)

Telarc CD-80283 56:57

Summary for the Busy Executive: An okay American. A mostly-beautiful Ab.

I might as well forfeit all my credibility and admit that I prefer Dvořák's string quartets to Brahms' – not all of them (some early examples definitely show the composer feeling his way), but the mature ones. Dvořák certainly has more of them to love, compared to Brahms' modest three. I feel Dvořák's ease and Brahms' discomfort in the form. It may have something to do with the fact that Dvořák was a string player and Brahms a pianist. Schoenberg once pointed out that Brahms' string quartets lay suspiciously well for a pair of hands on the piano.

A series of old Vox Boxes introduced me to Dvořák's chamber music and immersed me in his string quartets. I'd call the performances sturdy, rather than elegant or penetrating, and I kept on the lookout for other accounts. A revelatory performance of the "American" by the Quartetto Italiano on Philips bowled me over, and it's remained among my top five Dvořák readings. I never followed the Cleveland Quartet very closely while it was active – definitely my loss. However, I saw William Preucil, as concertmaster of the Cleveland Orchestra, do a Mozart violin solo and had to pick my jaw up off the ground. Not only did it sound unbelievably rich and Preucil phrase superbly, the physical act of playing was remarkable in itself. It was as if the instrument floated in the air and Preucil touched it only enough to hit the right note and move the bow across the strings. In comparison, other violinists, even very good ones, seemed to haul about a piece of lumber. So I decided to acquaint myself more fully with Preucil's work.

The "American" quartet in F probably qualifies as Dvořák's best known, perhaps because it's the only one with a subtitle. Of course, lively themes and rhythms help. In any case, there's very little "American" about it, aside from the fact that he composed it in Spillville, Iowa. In fact, its idiom sounds similar to that of the String Quintet in Eb, which he composed at roughly the same time and which doesn't get the same fuss. It starts off with a syncopated, pentatonic theme, which shares a family look with the opening to the "New World" symphony. Again, he finished the two works within months of each other. One can even hear a similarity among the second subject groups of the two works. The Cleveland plays with a big, rich sound and beautifintonation, and that's part of the trouble. They have a rather restricted dynamic range, particularly toward the softer end. It's beautiful but not especially subtle playing, short on atmosphere and a bit soft on the attack (not particularly desirable for dance rhythms). One may counter that Dvořák's music can take the bluff and hearty approach. I don't necessarily disagree, but I find the Quartetto Italiano's lighter, nervous excitement, building tension by keeping on the dynamic lid, a more penetrating, multi-faceted account – amounting to a successful rethinking of this composer.

The Ab quartet, Dvořák's last or second-last (depending on how you count), is more introspective than the "American," and the Cleveland, to its credit, responds to the difference. The interpretive subtlety missing from their other performance comes through here. Again, the key seems to be the refinement of the gradations of soft dynamic and their imaginative application. This is evident throughout the emotionally complex first movement and even in the scherzo, played by many quartets as a jolly dance with a tender trio. Even in the bolder sections, the Cleveland finds opportunities for softer, contrasting dynamics. Obviously, a lot of planning has gone into this performance. In the slow movement, the Cleveland seems to lose this fine focus just before the middle – or maybe I do. The notes just lie there, like a heavy meal, rather than lead anywhere. However, the group quickly recovers, finishing beautifully. The final movement delivers some wonderful surprises: the opening transition from the F Major of the slow movement to the Ab of the finale is gorgeously done, with intonation exciting in itself. Here and there, the rhythm momentarily dulls a bit, but the players catch themselves and pull up their socks. The climaxes blaze with the glory of the Mendelssohn Octet. You almost can't believe only four guys are playing.

The recorded sound is a bit much, for my taste. For chamber music, I prefer a slightly drier acoustic than what Telarc provides. Still, those who enjoy a good wallow might not mind as much.

Copyright © 2000, Steve Schwartz