The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Rouse Reviews

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

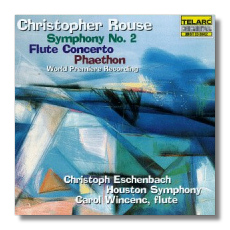

Christopher Rouse

World première Recordings

- Symphony #2 (1994)

- Flute Concerto (1993)

- Phaéton (1986)

Carol Wincenc, flute

Houston Symphony Orchestra/Christoph Eschenbach

Telarc CD-80452 65:29

Summary for the Busy Executive: Risky business.

Now in his fifties, Rouse has outgrown the Young Man of Promise label and become one of the most prominent of American composers. As far as I'm concerned, he deserves his success. His influences range from classic maverick George Crumb to scion of Modernism Karel Husa to academic serialist Richard Hoffman. From Crumb, he seems to have inherited a sharp ear for new instrumental sonorities, from Husa a sense of drama, and from Hoffman the ability to write a coherent long piece. His rather eclectic idiom is really no longer controversial, and he hasn't indulged for a while in the kind of conceptual stunts one might have alleged against some of his earlier works (eg, the nevertheless brilliant Gorgon). He still, however, takes risks, although he's left behind the superficial, easily apprehensible kind. In fact, they're bigger - his commitment to clarifying his artistic personality perhaps the largest of all.

After an early interest in loud sounds and in rock, Rouse has become more and more Romantic, in the same sense as a composer like Barber. He differs from Barber in that he doesn't seem able to come up with a genius tune, although his music brims full with memorable and affecting passages. He shares with Barber a dedication to individual expression and a sense of what music should do for you - music as the expression and engenderer primarily of emotion. I believe Rouse's music some of the most heart-felt now being written.

I began to view Rouse in this way with his trombone concerto (RCA 09026-68510), and the second symphony reinforces my impression. In three movements, played without a break, the symphony begins deceptively, as a more-or-less neoclassic toccata. As the movement progresses, however, it becomes gradually more disturbed and disturbing. Beneath the bubbling sixteenths an obsessive rhythm, a rat-a-tat on a repeated note with a semitone fillip on the end, adds to the feeling of desperation. The movement ends on the rat-a-tat shouted out by the orchestra. Abruptly we find ourselves in a dead calm of an adagio - Carlyle's Centre of Indifference. The death of composer Stephen Albert inspired this movement, which sings mainly of the numbness of grief. Beneath the keening, however, we gradually hear a variation of the obsessive rhythm of the first movement, growing more and more insistent and driving the orchestra to a massive outcry and (just when you think there's nothing more to give) an even more massive outcry, before subsiding once more into indifference. It's a long slide into practically nothing - a few soft strokes on the bass drum and fragments on a solo wind (heart and breath?). A quick crescendo leads to the third movement, which in a sense continues the first. Again, the neoclassic toccata percolates, but in the light of the adagio, with a hornet's rage. The semitone fillip is now an idea in the foreground - at times morphing into the B-A-C-H theme (B Flat Major A C B). At other times, the rhythm evokes that of the opening movement of Beethoven's Fifth. It ends with a series of hammer blows, with the volume way up.

Rouse pulls off the same trick as many great composers: he gets you to think of the emotions "behind" the notes. That is, one feels that music so powerful must mean something. The symphony's considerable skill serves the emotional wallop it delivers. He puts all his materials and maneuvers in plain sight, almost like the magician who obligingly shows you that there's nothing up his sleeve before he dumbfounds you. For a composer, clarity of procedure, idea, and intent are among the greatest risks, since you'd better have something worth saying. If not, the lameness will become apparent right away.

The flute concerto is a lighter affair, although one can scarcely call it lightweight. Rouse was inspired both by Celtic folksong and the death in England of two-year-old James Bulger at the hands of two older children, both ten. Here, among other things, Rouse shows what he can do with a melody. In the opening movement, the flute sings serenely against the orchestral strings in held chords. It's rapt, but I doubt you will remember the tune. I certainly don't. Nevertheless, it stirs my blood. The second movement bursts in abruptly, like revelers throwing open a door - a symphonic jig. The third movement, an elegy to the murdered child, is sad, but cool, working through the conventions of the musical elegy - the slow march, low, dark timbres, chorales, and so on. The melodic line begins dissonantly, but softly. Gradually, a chorale of great nobility (or rather a magnificent chord progression repeated over and over - it's so wonderful, I couldn't get enough of it) comes out of the orchestra - first for strings alone, then for brass, then for winds, separated by accompanied cadenzas for solo flute. For the woodwind statement of the "chorale," the flute joins in. The movement, haunting and poetic, ends on a pure "amen" cadence.

The fourth movement, yet another jig, dances in a marginally more folk-like way than its earlier counterpart. I hear little bits of Holst's "Mercury" sneaking in, but it wouldn't surprise me to learn that Rouse didn't consciously appropriate. The resemblance probably comes down to the character of the rhythm and the mercurial changes of orchestration.

The finale, like the first movement, has the flute singing against rapturous chords. It's not a song so much as it is the heart of song. Rouse seems to get down to the ancient power of music in this quiet finale, ending the concerto as it began - with a brief brush of the harp.

The earliest work on the disc, Phaéton, was inspired by the Challenger disaster. It's an effective, dramatic piece, but it does show in a way a young composer unable or unwilling to trust himself. Although the piece moves in a clear way, the ideas are a bit overly complex, the orchestration a tad too thick, and the percussion over-relied on. One sees the difference immediately between this and the symphony, a work no less powerful or capable but far more memorable, mostly because the composer has stronger faith in the worth of his basic materials. All that said, I can imagine composers wishing they had written it. The eclecticism of the piece (a fanfare on massed horns, for example, reminiscent of the finale of the Barber piano concerto) matters less than its considerable impact. It has the sole disadvantage that Rouse now would have done better.

Eschenbach and the Houston work wonders with this music. It can't be easy to play, and yet the rhythms are sharply articulated and the busy textures marvelously clear. I know very little about what constitutes a good flute player, so I really can't criticize Wincenc intelligently. She takes no horrible misstep, and the tone sounds good. On the other hand, most of my kicks in the concerto come from Eschenbach and the orchestra rather than from her. Despite these criticisms, this CD represents a highlight of my year.

Sound is Telarc's usual wonderful.

Copyright © 2001, Steve Schwartz