The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

- Latest Reviews

- More Reviews

-

By Composer

-

Collections

DVD & Blu-ray

Books

Concert Reviews

Articles/Interviews

Software

Audio

Search Amazon

Recommended Links

Site News

CD Review

CD Review

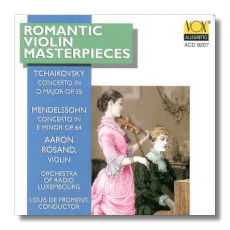

Tchaikovsky / Mendelssohn

Violin Concertos

- Felix Mendelssohn: Violin Concerto in E minor, Op. 64

- Piotr Ilyitch Tchaikovsky: Violin Concerto in D Major, Op. 35

Aaron Rosand, violin

Orchestra of Radio Luxembourg/Louis de Froment

Vox Allegretto ACD 8207 1996 ADD 58:01

Much has been made, especially in recent years, of Aaron Rosand's "unique" musical personality. He has been hailed as the last of the great romantic violinists (but then what are Stern and Menuhin?) and as a highly individual stylist (but then what is Kremer?). His fans have included Nathan Milstein, whom anyone would be proud to count as an admirer. But I remember the early recordings Rosand made for Vox in the late 50s – I bought them as LPs within only a few years of their release. At that time, he seemed only another blossoming young talent, not at all the flamboyant champion of the romantic repertoire he is now taken to be. And he hardly stood out from the crowd, neither generating Michael Rabin's virtousic electricity nor making so distinct (if derivative) a stylistic impression as Erick Friedman. Even then, though, he played repertoire that others for one reason or another disdained. His recording, for example, of Sarasate's Spanish Dances was a most welcome addition to the violinist's record shelf. And from that time to this, he has steadily built his reputation by playing what others no longer play – for example, Joachim, Goddard, Hubay, and Ernst (Ricci got into this game, too – and with the very same conductor).

Rosand brought to this enterprise a rich, buttery tone, which he nevertheless deployed with the austerity of a Cistercian monk (it may have been this chasteness that Milstein so admired). His somewhat heavy bow arm was coupled with a solid left-hand technique (reminiscent of Paganini's foil, Spohr), complementing an unerring sense of pitch. He had a tendency like David Oistrakh's to slow down in technical passages, adding extra weight to them, and a flair for the occasional dramatic, even eccentric, gesture. But the underlying virtuoso excitement of a Heifetz, a Milstein – or even a Szigeti – was always lacking; taking its place was the kind of benign placidity that now puts the final dehumanizing touch on the younger generation of contest winners. If it's there at all, Rosand's "ultra-romanticism" lies buried in the phrases and sentences, not in the paragraphs and chapters.

Still, Rosand is always worth hearing. He is not faceless like the generation of violinists that succeeded him. And he never fails to turn in a well-crafted, polished performance. He certainly doesn't fail to do so in these reissues of the Mendelssohn and Tchaikovsky violin concertos, originally recorded in 1972. Like most of his readings, these are rich in detail – he has discovered poetic moments in the Tchaikovsky's slow movement where others have found only prose, and he is commanding in the finale in passages where others are perfunctory. The Mendelssohn concerto is harder to personalize without risking mannerism; and, despite his reputation, Rosand on the whole is a classical rather than a mannered player.

Froment's orchestral accompaniment is no more than adequate, and the recording sounds tubby, with an annoyingly booming bass. But the violin is miked close up, so the recording'a deficiencies become really bothersome only in the tuttis. The spotlight is so consistently on Rosand, and he is so well deserving of it, that no flaw in the recording, so long as he is clearly audible, can be considered fatal.

These are not definitive recordings of the Tchaikovsky or Mendelssohn concertos. But they should have a strong appeal for two audiences. First, the super-budget price should make them excellent choices for those building an inexpensive collection of musical masterpieces. Second, all aficionados of the violin will want to have these Rosand performances (in fact, all Rosand performances – could Milstein ever have been wrong?). They will want them because Aaron Rosand is truly a violinist's violinist, in both the very best and the very worst senses.

Copyright © 1996, Robert Maxham