The Internet's Premier Classical Music Source

Related Links

Recommended Links

Site News

Koussevitzky Recordings Society

Fresh Perspectives on Serge Koussevitzky

|

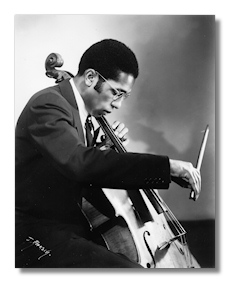

Kermit Moore at 18Photo courtesy Kermit Moore |

An Interview with Kermit Moore

By Victor Koshkin-Youritzin

VK-Y: What was your connection with Serge Koussevitzky?

KM: When I was eighteen years old, I received a John Hancock Scholarship to attend Tanglewood. There were ten such scholarships given that summer. They were announced on classical music stations, apparently all across the country. Relatives and friends heard the announcement and began calling my parents and me saying they had heard that I was one of the recipients of the award. Thus, it became public knowledge that I would attend Tanglewood.

VK-Y: What an honor!

KM: Regarding the award, the administration was very wise. They handled the funds well, being fully aware that they were dealing with young, inexperienced people. They put, basically, the large part of the money in a safe. If we needed funds, we would go to the office and fill out a voucher requesting a specific amount of cash. We would go and tell them that we needed a certain sum, sign our names, and our request would be granted. They didn't give us the whole sum at once, which was very clever of them.

VK-Y: Was that a whole summer at Tanglewood?

KM: A whole summer at Tanglewood, yes. That was my first summer, in 1947.

I became the first cellist of the student orchestra. I had auditioned in Cleveland when the Boston Symphony was there on tour. Jean Bedetti was one of the judges. He was the principal cellist of the Boston Symphony. He was a very volatile, emotional person who was dedicated to perfection and artistry in the same manner as was Dr. Koussevitzky. Bedetti accepted me as a private pupil.

VK-Y: So it was actually Bedetti who auditioned you and not Koussevitzky himself?

KM: It was Bedetti plus a few other orchestra members. It was not Koussevitzky. I was presented to Koussevitzky when I got to Tanglewood. Koussevitzky was very thoughtful, very helpful and extremely kind because he didn't try to appear as formidable as he really was. When you met him, he was scary, I thought – partly because of his stance. It was a kind of autocratic stance that had to be interpreted by a teenager as a little standoffish. But he was not standoffish. In fact, he had a great sense of humanity and humor. It was a new experience for me in every way except for being first cellist of the student orchestra, because I was coming from the Cleveland Institute of Music where I was also the first cellist of the student orchestra. And I was already dabbling in conducting because Beryl Rubinstein, who was the head of the school, gave me some sessions in conducting. In fact, in my senior year he asked me to conduct the fourth symphony of Beethoven. Rubinstein coached me in the work. Conducting it was an experience that never left me. I often program it when I am engaged as a guest conductor. I frequently build programs around it. I conduct less frequently now, but my yardstick for efficiency remains the lessons learned from Koussevitzky. He inspired me and everyone who was near him. He was a very articulate person in a very eccentric way. Obviously, he had a strong accent, and some words were hard to understand. Just a quick side-step to give a little story. Koussevitzky was having a meeting of the Student and Faculty Committee for the activities at Tanglewood that summer, and he said to us (I was one of the student committee members): "We're going to have a paghann, and who will help me?" But we didn't know what he meant. And he repeated it, and nobody volunteered because still nobody knew what he meant. And, so, finally Boris Goldovsky, who was a faculty representative, said "Oh, pageant!" Then everybody volunteered to get involved in the pageant. But that kind of language was just amazing to me. He could create words in a most eccentric way, and yet he was extremely articulate. I attended many of his rehearsals. In them, he would make statements that were humorous but also very serious because nobody could risk taking him in any other way than serious. He said once to a clarinet player, "If you will sleep, go home. I can assure you will rest more comfortable." And so I wrote that down.

VK-Y: Did he treat the players of the student orchestra differently from his own Boston Symphony players?

KM: It didn't appear so. I think, in general, in his initial approach he was always a little bit gentler with the students. But by the time we had begun to dig into a work, he was very demanding, very strict, and often impatient.

VK-Y: So that was actually basically the same approach as with the Boston Symphony.

KM: That was the same. His initial actions were a little bit gentler, but I think that basically it was the same Koussevitzky with everybody.

VK-Y: Did you see him interact a lot with the Boston Symphony itself?

KM: Oh, yes, as often as possible.

VK-Y: How many weeks were you there that summer?

KM: Eight weeks. I think they've shortened now, but it was eight weeks – July and August.

VK-Y: What pieces did you play then as first cellist? I recall my conductor friend Anthony Morss saying you performed the Saint-Saëns cello concerto.

KM: I played his concerto with the orchestra. As a member of the orchestra, I also performed a work that was so unforgettable to me. That was Tchaikovsky's Francesca da Rimini. It's a very difficult work to begin, but I noticed Koussevitzky had no difficulty in getting it started. What I also observed was the vein on his forehead. The vein seemed to become more prominent. His eyes became more fiery, and his arm would rise, and down it would come, and everybody was right with him. It was as if a magic button had been pushed.

VK-Y: How beautiful!

KM: So I actually asked him about the beginning – how he managed to do that – and he said, "Moore, you play when the hand strikes the air." And so I put my hand in the air as if I were going to give a down-beat, but at what point did it strike the air? That was the mystery to me. And so I held my hand up, and he said, "Do you know the word 'anacrusis'?" and I did. I said, "Yes, that means the upbeat." He said, "So nothing is more important than the upbeat." That was the first bit of advice he gave me. He aided me in developing an efficient method of giving a clear preparatory beat. I questioned him about the opening of Francesca da Rimini. The reason that I was able to ask him was that I was trying to lead my section, and I thought it was a legitimate question. How do we start? He was so clear, and it was so very, very foolproof that I was extremely impressed. And so, that stayed with me all through the years, and when I was in the von Karajan master class in Milan with the La Scala Orchestra, I was, as was customary, assigned a musical problem to solve by him. My problem was to conduct the opening of the Piano Concerto in G of Maurice Ravel. The work is a challenge, particularly in the opening. That's another extremely difficult work to begin, and von Karajan had given it to me for that reason. He wanted me to solve that problem. And so I came and I conducted the opening, and he said, "You're not ready. You're not ready." And I didn't know quite what he meant that I wasn't ready. He said, "You're not singing. You must be singing long before you give your upbeat." I thought that was very astute, and it reminded me of Koussevitzky, who was always singing so much before he gave the downbeat that it was not as if it were a downbeat – it was a continuation.

VK-Y: When you say singing, you do not mean actually literally singing.

KM: No, no, it is in his mind. It is in his mind. And so he told me I should be singing the opening in my mind long before beginning to conduct. And so I just knew that Koussevitzky felt the same way.

VK-Y: It's absolutely fascinating to have your comparison between Koussevitzky and von Karajan.

KM: I had learned from Koussevitzky, and I have imparted his advice now to everybody who seeks my advice. For example, there are so many works that require – and so many movements of works, scherzos and things of that nature – that require a very clear, cogent downbeat, and Koussevitzky had that better than anybody I've ever seen. His players were already in the midst of performing the movement. They weren't just beginning anything. The piece had begun moments before in their own minds, in their perceptions. That was a lesson for me for everything.

VK-Y: I find your comments here extremely interesting because there has been criticism over the years about Koussevitzky's conducting technique.

KM: Some people said that there was not enough clarity. I totally disagree with them. I thought he was as clear as anybody I've ever seen before or since, and I have played under Stokowski, Szell, Bernstein and a lot of other people – Franz André in Belgium, and von Knappertsbusch in Germany. I've played with a lot of conductors, and I think that the only word to use for Koussevitzky was eccentric, not unclear.

VK-Y: What you're saying is very important for the historical record.

KM: So very, very clear, but what is amusing though, in retrospect, is when he would say, "Play when the hand strikes the air." That for me is something I can't forget because I've always been trying to discover, "When is my hand striking the air?" The result is so perfect that you just can't argue with the concept over the statement.

VK-Y: I wonder if the players in the orchestra mentally themselves somehow tuned in to Koussevitzky's wavelengths before something would start.

KM: I'm sure they did….An important element in the Boston Symphony at the time was Richard Burgin, of course. Burgin was the concertmaster, and he was very self-effacing in some ways, but so responsible. He had such a sense of responsibility. He brought his section in all the time because he did so much of the rehearsing that they were accustomed to following him anyway. Whenever there was a new work, it was Burgin who was leading the rehearsal, and Koussevitzky would come in after the orchestra was broken in, so to speak, and then he would take over the rehearsal. That would be days later. Burgin was one person whom everybody in the orchestra followed and looked at constantly.

VK-Y: I wonder if he has gotten as much credit as he should have in this regard.

KM: I always felt that he got no credit. I don't think he even particularly wanted it. He was very serious about his job. He played very beautifully, and here again his sound was a little bit unusual, but it was always in tune and always strong.

VK-Y: When you say unusual, what do you mean?

KM: I thought his violin sound was a little bit brittle, even though he had a marvelous violin. I can't remember quite what it was.

VK-Y: And that would be odd for the Boston Symphony, since the orchestra had such a rich tone.

KM: Indeed, tone was such an essential factor. Burgin, on the other hand was very important to Koussevitzky also. He was an assistant conductor par excellence and a very fine leader as the concertmaster. I asked him many questions, and he was very patient, very fatherly. Burgin was a small person who loomed large on the podium, and you hitched your wagon to his lead because he always was leading so successfully. That was his great triumph.

VK-Y: Wasn't Koussevitzky in a way the same?

KM: I still don't know anybody else quite like Koussevitzky. He would wear a cape often. He would wear a cape, and he would take it off and with his right hand seem to be handing it off to nobody in sight.

VK-Y: That's wonderful.

KM: But you swore that before it would hit the ground someone was going to catch that cape. He never even looked around to acknowledge the transfer. I never saw him say "Thank you." He just took the cape off and handed it off to some very rapidly appearing person.

VK-Y: Well, again, he was in control of the air, I guess you could say.

KM: He was extremely dapper, and the capes were always very attractive. I've known several other conductors who took up the habit of wearing capes because of Koussevitzky. One of them was Dean Dixon. In the dead of winter, he would wear a cape, and I always thought that was incommodious, but he would always wear his cape, and that was a Koussevitzky signature.

VK-Y: Do you remember anyone else who…

KM: Leonard Bernstein wore a cape.

VK-Y: Of course, Bernstein, sure. Did you know Bernstein particularly well?

KM: I certainly respected his achievements. I will tell you an interesting story. I was conducting the Symphony of the New World in Lincoln Center's Avery Fisher Hall. This was 1974, and Bernstein was no longer the conductor of the New York Philharmonic, but he was guest conducting this particular concert and there was a rehearsal in the hall the morning of our rehearsal, which was scheduled to begin at 2:00 in the afternoon. 1:30 came, and I couldn't get my 104-piece orchestra on stage. They were all milling around backstage because Bernstein was still rehearsing the New York Philharmonic, and I didn't know what to do. It was going to cost the organization tremendous amounts of money if I couldn't get the orchestra on stage in time to start the rehearsal. So here's what I did: when one of Bernstein's orchestra members walked off the stage and the door leading to the stage opened, I just walked in and stood inside, and Bernstein looked up, saw me and said, "Is that Kermit?" And I said, "Yes." And he said, "What are you doing here?" And I said, "At the moment I'm losing money."

VK-Y: What a great answer!

KM: And he started laughing and said, "Everybody off the stage! Everybody leave quickly! Kermit's losing money!" He got the orchestra off in about five seconds, and we were able to begin our rehearsal.

VK-Y: That's magnificent.

KM: He was so thoughtful in that way. He was very upset that he was causing us this worry. Later, I reminded him of that when Carnegie Hall was reopened after having been closed down for repairs and refurbishment. I participated in that event. Bernstein was there with his bad habit of chain smoking. There was a young man who took his cigarette as Bernstein walked on to the stage. He handed the young man the cigarette he'd been smoking, he went out and conducted, and he came off, and the young man handed him another lit cigarette. And I thought that's a pity. I'm not judgmental, but I just felt that he could have known better – that that was going to destroy him, and it finally did.

But to answer the question, did I know him? Yes, he was very helpful to me in my two years at Tanglewood. He helped me with dealing with the cello section, dealing with the orchestra, and dealing with the repertoire. And he was always asking, "Do you need any help? Is there any problem? Do you have any problem?" I thought that was extremely magnanimous of him.

VK-Y: Well, that's great! What was his specific role that year at Tanglewood?

KM: He was an assistant to Koussevitzky. He was a faculty member. And speaking of the faculty members of the Boston Symphony for Tanglewood, I don't think there's ever been anything quite like it. My coaches for chamber music at Tanglewood included Gregor Piatigorsky, William Primrose, and Richard Burgin. I don't see how one could do any better. It was just wonderful. I was doing the Opus 22 of Hindemith, the String Quartet, and William Primrose was the coach, and Norman Carroll, who later became the concertmaster of the Philadelphia Orchestra, was playing first violin in the quartet. This was shortly after I had played the Saint-Saëns concerto, and I hadn't had much time to practice the Hindemith. Primrose didn't want to hear any excuses. He said, "Tomorrow, memorize, you will have between now and tomorrow – you will have memorized the first movement." And so the rest of that time I practiced the Opus 22, and finally, when I realized I knew it from memory, I got to the session the next day ready to play it from memory. Primrose never even looked to see if I was playing from memory or not, because he knew that all he was urging me to do was practice it. And so I practiced it well enough, assiduously enough, to play it from memory. And he never looked at me, never made a comment about it – he was just satisfied that I had learned my lesson that priorities are priorities, and you can't forget that.

VK-Y: Well it's too bad he didn't see that you had it memorized.

KM: I'm sure he saw it, but he wasn't going to acknowledge it. I don't think he wanted to be triumphant about it. He also didn't want to be too cloying about it. He didn't want me to feel that I should have a star put on the refrigerator because I had done something noble like memorize my part.

VK-Y: Still, it might have been a nice boost to a student to have that acknowledgement, after all.

KM: Well, Piatigorsky gave me one lesson per week, and there again, for each lesson, I would have to go into my safe in the office to get out this small amount of money that Piatigorsky charged me for a lesson. And when I say small amount of money –

VK-Y: What was it, if it's not confidential?

KM: Ten dollars.

VK-Y: Excuse me?

KM: He charged me ten dollars to have a lesson that lasted probably an hour and a half.

VK-Y: Wow! I don't know what that is in today's money, but it's still a pretty good price. What was he like in your recollection?

KM: In fact, he did not like my cello and he started a campaign. He even wrote to my parents to urge me to get me another cello. A letter appeared in the Cleveland Plain Dealer that Piatigorsky was leading a committee to find the right instrument for Kermit Moore. An instrument was eventually found.

VK-Y: Well, how wonderful!

KM: My parents, of course, had to pay for it, but the price was reasonable. It was a Tononi cello, and it was just exactly what I needed. My cello was called a Nemeth Barat. Nemeth Barat was a Hungarian luthier. I liked my earlier cello, but Piatigorsky didn't like it. I felt that his wisdom should prevail, and I got the Tononi from Paulus Pilat, a luthier in New York. My father found out the price and wondered if it was worth it. And I said, "Oh, it's going to be worth it." He then bought it for me.

VK-Y: What was the price, do you remember?

KM: It was a bargain. It was $6,000.

VK-Y: $6,000, and we're talking about what year?

KM: By this time it was 1948, and my father had never spent that kind of money on a cello before, because I think the cello that I owned cost $500 or something like that.

VK-Y: And it was still good enough to get you as far as you had gotten at that point, though.

KM: I thought the cello was quite good. First of all, it had a robust tone. I wanted to have a large tone. The Tononi was mellower. In retrospect, the Barat might have been a bit brash. One can make an impression with a big sound. On the other hand – the other side of the coin – one should seek a more sensitive, refined tone.

VK-Y: Right.

KM: And that's what Piatigorsky felt, and that's why he started this campaign.

VK-Y: Yes. And that would tie in again with the Boston Symphony, because Koussevitzky was such a fabulous colorist and master of subtle tone.

KM: My one large extended conversation with Koussevitzky was about Mozart's Jupiter Symphony. The Boston Symphony Orchestra had played it, and I attended all the rehearsals and performances. I walked up to Koussevitzky, and I said, "That was the most beautiful performance of anything that I've ever heard." As far as tone was concerned, as far as interpretation, and flexibility, I thought it was wonderful. He stopped right in his tracks, and he said, "That's very kind of you." Well, I wasn't trying to be kind – I was just so bubbling over with enthusiasm. And I was – I guess there's a word for that – babbling probably. I was just babbling away about how wonderful it was, and it really was. But he was very touched by my sentiment. I appreciated his very generous reaction.

VK-Y: That's a lovely thing to know.

KM: Well, one day he was driving across the lawn. His was the only car allowed inside the grounds. He was in the car with Victor his chauffeur, and Koussevitzky beckoned to me. I walked over to the car, and he said, "You will come to the house for dinner tonight." And I said, "Thank you very much, I'd love to." He said, "Victor will pick you up." I stayed at Tracy Hall, which was the dormitory, and he said, "Victor will be down there at about 6:00, so be outside at 6:00." He said, "Victor, what are we having for dinner?" And Victor said, "Oh, I imagine beans." And Koussevitzky said, "Yes, beans, we always have beans," and they began to laugh. Well, of course, we didn't have beans, but that was just a joke of his. I got to the house, and we had a wonderful conversation. We talked about Ravel, I remember, and we talked about Bartók.

Somebody has since then told me a story that moves me very deeply, and that is that Bartók was a very proud man and a very impecunious man at the same time. He had just no income to speak of and just no money. He was sick as well, and somebody told Koussevitzky that Bartók was very sick and had to be hospitalized. This we learned from Joseph Conlon, who knew both Bartók and Koussevitzky. For just a little footnote, Joseph Conlon is the most recent President of the New York Musicians Club, of which Olga Koussevitzky was one of the leading members. She had been President for something like twenty years. The New York Musicians Club was founded by Walter Damrosch in 1911. We haven't had very many presidents because our presidents serve such a long time. While Joseph Conlon only recently became President, he years ago told me this story that Koussevitzky was warned, "Now don't go to see Bartók and offer him money because he won't take it. He'll be very insulted, so you'll have to do it some other way." Koussevitzky then went to see Bartók in his hospital room and offered him a commission to write the Concerto for Orchestra. This was 1942 or '43. This was the story that I was told by Joseph Conlon. Bartók accepted the commission. He would not have accepted a gift or a loan, but he then launched into the Concerto for Orchestra, which was I think his last work of significance. It was very generous of Koussevitzky to be that sensitive to find a way to get Bartók the money that he needed.

VK-Y: Turning back to Tanglewood, what did you most get from your experience at Tanglewood as far as Koussevitzky was concerned, and what did you get that actually lasted you a lifetime and that you then perhaps even imparted to other people?

|

| Moore and the orchestra he founded, The Classical Heritage Ensemble, at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine, N.Y.C. 1996 Photo courtesy Toni Parks |

KM: Well, there is something that I do every time that I conduct any group – my own, which is called the Classical Heritage Ensemble – or any other, such as, at one time, the Brooklyn Philharmonic Orchestra or the Detroit Symphony or often in San Francisco the Berkeley Symphony, and places in between – I was in Dallas recently conducting the Chamber Orchestra for the second time. Every time I stand in front of an orchestra for the first time, I make myself think of Koussevitzky. First of all, because of the way he stood there – there was such authority in his stance – I mentioned something about his stance earlier. There was something about him that made him a giant practically. He was not a tall man at all, but he stood there with such authority and there was no waste, there was no dross. It was just all gold, his motions, his movements. And I felt that this was something that could take me a long distance when it comes to conducting. Don't waste your time; don't waste your movements, your motions; don't waste your voice; be effective and efficient, succinct and to the point. Koussevitzky was like that. I remember writing a number of things that he would say to the orchestra. "Put the bow in the string," he would say. "Put the bow in the string." Well, the bow's on top of the string, but you have to have the concept, at least in his eyes – you had to have the concept that the bow was actually in the string, and that you're kneading it as if it's practically malleable or as if it were pliable like clay or putty, so that you're into the string, you're getting all the yield you could possibly derive from the string. I've never forgotten those things. I got a lot of those same things from von Karajan on a much briefer level. He was also somebody who never wasted words, and it was just as well because my German wasn't all that good anyway. But he was extremely helpful. Everything he told you had a purpose.

Returning to Koussevitzky – everything that he said had a purpose, and he would tell people things that just related to them personally. If you have seen a Mahler score, Mahler would give in the score instructions to the player – individual instructions to the individual players. There might be a little statement he would make to the first clarinet or the bass clarinet, or the first horn or the fourth horn, or the eighth horn since it's Mahler, and he would give all these instructions that you could hardly find the notes, if you look at those early scores – the way they were initially printed. I learned German from reading and translating the scores of Mahler symphonies when I was about fifteen or sixteen. I would put my German dictionary inside the Mahler score, and I would make sure I could be responsible for every word. There were so many different statements that he made to so many different players that it was a lot of clutter, but I certainly managed to learn something in German that way and also the scores as well. Koussevitzky wasted no words, but he said words in his own way. "First clarinet, you are not together," was one of the things he'd say, and we all laughed. Koussevitzky was extremely humorous. He probably didn't even realize it.

VK-Y: Do you think most people in the orchestra appreciated his sense of humor?

KM: Yes. I think the people in the orchestra – well, first of all the Boston Symphony, I couldn't say at all. I was just a boy, you know, I was only eighteen. Seventeen or eighteen. The last time I was there I was nineteen, so I don't know what they really thought. I just can tell you the quickest story I suppose. Jean Bedetti became very angry with Koussevitzky because Koussevitzky had the temerity to say things to Bedetti: "Bedetti, your notes don't sound. They don't sound." And Bedetti said. "Maître, which notes don't sound?" And Koussevitzky said. "The whole thing. The whole thing. The notes just don't sound," and so Bedetti was so angry he stormed off the stage. He walked across the stage and management had to ask him to come back and he refused. So they asked Koussevitzky if he would apologize to Bedetti. Koussevitzky said, "No, I will not apologize. He will come back." And Bedetti eventually did come back, apologetically. He apologized for storming off.

VK-Y: Considering today's conductors, what do you think they could learn from Koussevitzky through listening to his recordings?

KM: They should learn to listen. I know a lot of conductors who are formulaic and doctrinaire. I don't think they really listen. They have a speech to make. They make their speech. They have a pose to take, and they take that pose, but very few are in the category, let's say, of the recently deceased Klaus Tennstedt, who was a wonderful conductor. And as long as Carl Maria Giulini was functioning, he was with the old school conductors.

In fact, Tennstedt had just finished his studies with von Karajan when I was in Milan with von Karajan. Tennstedt was already a young budding conductor. Von Karajan was very, very clear in everything. No wasted speech. Also there was a phrase that I liked very much that Koussevitzky once made, "The more you press, the less you get." And he was talking to the string players.

VK-Y: That actually applies in sports, too.

KM: Exactly. It certainly does apply. And he would admonish us all, "Don't press, don't squeeze, don't choke your instrument." And that was very good advice, and I still feel that way. I just played a recital here in New York, and it was in a wonderful hall that belongs to New York University called Tenri Cultural Institute. I played there other times as well. I really liked the hall. I have a Cremonese cello. I know that if you have the gall to press on a Cremonese cello, it's going to say, "Leave me alone." It won't accept that. Well, I came from a Gofriller cello – a Tyrolean instrument – to the Cremonese cello. For the first few months that I had my Ruggieri, I was pressing a little bit. But that was years ago, though, and I learned my lesson – you don't press, not with the bow, not with your hands. Just treat the instrument with respect.

VK-Y: That applies also to a piano – to a pianist's touch.

KM: Oh, it does apply to the piano, sure. It's very important in singing. If you're singing and pressing you're very unsuccessful. You can't sing if you're pressing. It becomes a hard, unyielding sound. And so that's just something that you have to avoid. Koussevitzky got so much beauty out of the orchestra. I heard a performance of Daphnis and Chloé when I was at Tanglewood, but I'm going to start at the beginning with the Boston Symphony, because I think that's where most stories should begin.

When I was fourteen years old, I was an usher at the Armory in Akron, Ohio for the concerts that took place there. That was the big concert hall. It was called the Armory. In fact, I think it had been an Armory. The Boston Symphony came to Akron on tour, and I was one of the ushers. But my assignment that particular evening was the stage door. I would tell the players where they had to go. But, of course, just the orchestra members were arriving between an hour and a half-hour before the concert. By the time the half-hour call before the concert arrived, all the players were in, so my job was, in a sense, over until I took my station in the hall as an usher. I was an actual usher in the hall. Well, I met Jean Bedetti then without realizing I was meeting the first cellist of the Boston Symphony. I noticed they were all on stage early, very early, and they were practicing, and that's when I heard the Daphnis and Chloé. It was phenomenal. It was just unbelievable. I had never heard anything like it even though I grew up in the home of the Cleveland Orchestra with George Szell. I found that the Boston Symphony Orchestra had achieved great, beautiful sonority. George Szell was, in my opinion, certainly a wonderful conductor. Some things Koussevitzky did had more magic, I felt. And Koussevitzky's orchestra sounded like no orchestra I had ever heard, and I was determined to figure a way to make some of those same sounds as a cellist and to try to conduct in the same manner once I became a conductor. So that was a goal I made for myself. This is something I really must do, I felt – that was to get the best possible sound – and I'm going through this right now with a pupil of mine who is looking for an instrument, and I think he's found it. He doesn't quite know it yet. I think that he will realize it soon because he's still playing the new instrument in the old way. So, before he puts any money on it, he's going to have to be convinced that this is the instrument for him. I told him I'm not going to proselytize. I won't tell him this is the one you must get. But I think that he's going to realize it, and I'm very concerned about sonority.

VK-Y: Where did you say you were teaching this summer?

KM: At the Chamber Music Conference and Composers' Forum of the East it's called, and it takes place at Bennington College in Vermont. This is something that I've been doing for twenty-one years. The Conference has been there since 1946 in the summers. And when I go there, I always have a little sermon to give and that is, "Make the most beautiful possible sound. Don't make ugly sounds unless the composer asks for them."

VK-Y: Haven't we lost something of that attitude in today's culture?

KM: Oh decidedly. That's why I'm on a mission to return to that. It's just been unfortunate. There are some people who are dedicated to maintaining the responsibility – that they are maintaining the culture of it. I think Anne-Sophie Mutter is one of those. She is a violinist who loves sound and who is dedicated to making the most palatable sound.

VK-Y: Wouldn't you say that it's almost perverse of so many people to turn their backs on beauty of sound and just beauty in general? I just want to say something about my own field, visual art. Many professionals, for instance, in the art world have in recent years have been discounting beauty, saying that beauty is passé.

KM: Oh, I know.

VK-Y: Or they consider that artists producing work with spiritual content are passé. Well then who needs art, if it doesn't embody some of these high values?

KM: This is its spiritual content. And if they don't think that, they should do something else.

VK-Y: Exactly.

KM: Well, I feel that very, very strongly, and there are a few people whom I admire.

VK-Y: Do you want to mention them? That would be great.

KM: Unfortunately, there aren't many cellists. There is a Dutch cellist named Pieter Wispelwey. His chapter is just before mine in a 2001 book called 21st-Century Cellists. It has Yo-Yo Ma on the cover, and there are some interesting talents in the book. But Pieter Wispelwey – I've heard his Dvořák concerto recording, and I think it's wonderful. It is truly outstanding, and he is one whom I would recommend as a person who is dedicated to the search for sound. The violinist, Anne-Sophie Mutter, is one I would definitely recommend, and I think Joshua Bell plays with a wonderful sound. If people want to hear him at his best, they should listen to the Mozart Rondo in D for Violin and Orchestra. I feel that is his best playing. I've liked several things that he has done in recent years. I think that his reason for living is to make a wonderful, articulate sound with some kind of quality to it. There are not many pianists who focus on sound. One of them, strangely enough, is Maurizio Pollini. I think that he gets an extraordinary sound.

VK-Y: Yes, in his Chopin Etudes, for example – I think they're fabulous.

KM: I agree with you. I think I'm spoiled because I had all the recordings of Dinu Lipatti, and that is how pianists might fashion themselves in my view. They should all try to be like Dinu Lipatti. I also am very, very fond of the playing of Sviatoslav Richter.

VK-Y: Oh, I think he was wonderful.

KM: Wonderful.

VK-Y: For example, Richter's Rachmaninoff Second Concerto and Preludes are right up there with the composer's own level of playing. And I think that Richter's reading of the Second Concerto with Wislocki and the Warsaw Philharmonic is even finer that Rachmaninoff's own 1929 recording with Stokowski and ranks on a level with Rachmaninoff's exquisite, moving, and far less known 1924 acoustic performance of the concerto. And I love Richter's performance of the Dvořák Piano Concerto – in fact, that's by far the only truly satisfactory performance I've ever heard of it.

KM: Yes, I disliked the work until I heard him play it.

VK-Y: Since we were earlier talking about cellists, I wanted to ask your opinion of Pierre Fournier, who has, I think, as fine a recording as there is of the Dvořák Cello Concerto, with Szell and the Berlin Philharmonic. Do you know that performance?

KM: Oh, I certainly do. Because Pierre Fournier had been a pupil of Paul Bazelaire, who was my teacher at the Paris Conservatory. Once I was at lunch with Bazelaire, and his guest of honor was Fournier. And something that you just don't expect happened – they played a concert together with Bazelaire, this great cello teacher, this great cellist, one of the great cellists of the early part of the 20th century. He played the piano for Pierre Fournier. They played the sonata opus 102 no. 2 for cello and piano of Beethoven. They played the Debussy sonata, and it was most exquisite. Fournier was, for me, one of the most eloquent cellists of our time.

VK-Y: What do you think of Yo-Yo Ma?

KM: I think Ma is very fine. I think he does a lot for the popularization of the cello. He certainly has an extraordinary facility. I believe that Yo-Yo Ma will continue to be considered one of the more important string players. And I think that he deserves the respect of cellists everywhere.

Turning to other considerations, when I first encountered the Boston Symphony and Jean Bedetti and heard Koussevitzky, they did the Daphnis and Chloé Suite No. 2. I had heard nothing quite like it – the performance, that is – and so I went and got the score and started to study it, and this is the reason I'm telling this story.

VK-Y: Yes.

KM: I discovered Chinese cymbals, or Crotales. And I have used them in a number of compositions as a result of that. It was the most heavenly floating sound. Koussevitzky made very certain not to allow the use of Crotales to be obfuscated. He let them sound so well, it was hauntingly beautiful. Most conductors have this right in the palm of their hand, and then they allow it to be covered up by too much instrumentation around them. It was the most successful balance.

VK-Y: I have never heard any better interpretation of the piece than Koussevitzky's.

[Readers can hear his great performance of the work – recorded on November 22 and 27, and January 3, 1945 – on a 1993 RCA Gold Seal compact disc, number 09026-61392-2, with program notes by Tom Godell.]

KM: That was his concentration – he concentrated on balance so wonderfully, but at the age of 14, all I knew is that I was hearing sounds in a way that I had never heard them before. I was so impressed that it haunted me.

VK-Y: Yes, and that's amazing since you say that you were already listening to George Szell at that time.

KM: Because I was in school at the Institute of Music, and Szell was the conductor of the Cleveland Orchestra. I heard Szell more than I heard anybody else. And he was very imposing.

VK-Y: Now, did he ever do the Daphnis? I don't think there's a recording of that, is there?

KM: I have never heard Szell do Daphnis and Chloé. I heard him do some wonderful things but I never heard him do that.

VK-Y: Are there other aspects of Koussevitzky that affected you, or that you think would be important to direct our readers' attention to?

KM: Yes, I would like to say that his repertoire also pleased me more than most. He conducted the Tchaikovsky symphonies, and he passed the test, so to speak. He was able to put himself on the line, put his character and reputation on the line, as a conductor, by the "Little Russian" Symphony. By the 4th, 5th, and 6th symphonies – those works meant something to him, and so as far as conducting Tchaikovsky was concerned, I thought this is the greatest person to represent Tchaikovsky. And interestingly enough, I hear Tchaikovsky in the Chanson Triste of Koussevitzky, and in his bass concerto. In general, I hear the influence of Tchaikovsky in Koussevitzky's compositional output and in his style of articulation.

I think that he must have been really haunted by Tchaikovsky to the point of emulating him in many respects.

VK-Y: Well, I think that makes sense. I've never heard a greater performance of, for example, the Tchaikovsky Fourth than Koussevitzky's grippingly intense April 1949 recording.

KM: Oh no. It is overwhelming. And what about the Beethoven 9th Symphony?

VK-Y: I don't have a Koussevitzky recording of that. [Please note: Tom Godell has written to me that there is an RCA LP of the Koussevitzky Beethoven 9th and also a French broadcast of the 9th with Koussevitzky that Godell calls "a truly stunning performance (although) the recording has several serious flaws."]

KM: I heard Koussevitzky conduct the 9th Symphony, and I have never gotten over it.

VK-Y: Yes, that's what our conductor friend Anthony Morss once told me – he heard a live performance of the piece by Koussevitzky and said it was out of this world.

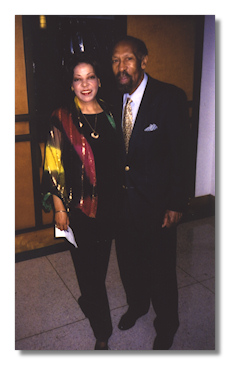

|

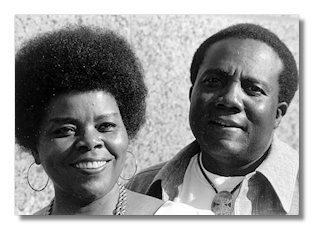

| Carol Brice and Thomas Carey, faculty members, University of Oklahoma School of Music Photo courtesy of Sooner Magazine |

KM: It was. Koussevitzky got a pianissimo that has never been achieved before, I'm sure, or since. He was able to make the basses and the cellos play pianissimo using the full bow. But he had them playing upon the string – in other words "flautando." And it was the most haunting sound, and at the same time, where he needed true grit, he got it. The piece opens in such a way that you think you're on a different planet. That's the opening of the Beethoven 9th symphony that I always thought was important. He was able to get that with such ease. I can tell you when that was. That was in Boston in 1949. Also he conducted El Amor Brujo with Carol Brice.

VK-Y: Oh, she was on our faculty here at the University of Oklahoma.

|

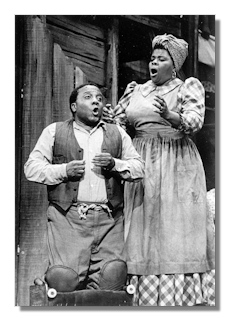

| Thomas Carey and Carol Brice in "Hello, Dolly" Photo courtesy of Sooner Magazine |

KM: Was she? You're kidding!

VK-Y: No, and I knew her. She died many years ago. She was married to another magnificent singer – and a great gentleman – Thomas Carey, who was on our faculty for many years. We have an excellent School of Music at the University of Oklahoma. Carol was a terrific person.

KM: Well, that's wonderful. I didn't know what had become of her. She had a brother who also died, whose name was Jonathan, who was an accompanist here in New York, and my wife used him as a rehearsal pianist and a vocal coach when she was just beginning to sing. You know that my wife, Dorothy Rudd Moore, is a composer?

VK-Y: Oh yes.

KM: She's done a lot of voice, you know, a teacher's voice.

VK-Y: I was going to ask you about her later in our interview.

|

| Thomas Carey and Carol Brice in "Porgy & Bess" Photo courtesy of Sooner Magazine |

KM: Oh great, we'll talk about her.

VK-Y: Now Carol Brice must have been magnificent in the da Falla piece there.

KM: It was incredible. Incredible. I attended the concert. I think there is a recording of Koussevitzky and Carol doing it. Koussevitzky said Carol Brice had a voice like a cello.

As far as other performances by Koussevitzky are concerned, the 9th Symphony of Beethoven was on a par with Koussevitzky's Jupiter of Mozart. There was absolutely nothing wrong with his 9th. There was just nothing but heavenly inspiration. It was gorgeous, every sound, every… his whole purpose was correct, I think.

VK-Y: I feel that also with Koussevitzky's unparalleled Harold in Italy. He establishes an extraordinary mood from virtually the very first note.

KM: It's gorgeous.

VK-Y: This mood that's established is just so completely gripping. Do you agree?

KM: Yes, I do totally agree.

VK-Y: That's that great Primrose recording, of course – much better than Beecham's with Primrose.

KM: Yes.

VK-Y: Koussevitzky's Harold is just, again, out of this world. And there's a provocative point that Anthony Morss once made to me: he said that Koussevitzky and Primrose make that piece better than it is.

KM: My problem with the piece is that there are so many long expanses without the viola playing the solo. And there are so many moments when you forget that's it's a viola solo work altogether. I consider it a tone poem featuring occasionally the viola. But what Koussevitzky made out of it was an entity that was much more engaging than it's usually made, but I think the piece has flaws. In general, I find the orchestration of Berlioz was a tiny bit too treble for my taste. I long for more lower register utterances. I should really be probably saying it's too treble, except when the viola plays, and for me that becomes a mystery to the listener. He might not even know what's bothering him. I think that what's missing is lower register orchestration. I just absolutely love that Koussevitzky and Primrose performance. Primrose was the best for it I think. He was really a very, very thoughtful player. I felt bad about his hearing toward the end of his life because his whole purpose was to be able to play and make the sounds he wanted to hear, but he became so hard of hearing that if you were standing behind him and yelled out his name, he wouldn't turn around. He wouldn't have heard you. It was a pity because that was a great loss.

VK-Y: With Harold in Italy, I just wonder whether just logically is it really valid to say that a conductor can make a piece better than it is – maybe it's just that no other conductor has ever performed the piece the way it should be, unless he's improving it by improvising and changing notes and passages. Do you see what I'm getting at?

KM: Well, I do. I don't think that's possible to make it better than it really was in the mind of the composer.

VK-Y: So basically Koussevitzky met the mind of the composer.

KM: He met the mind. He was expert at penetrating the mentality of the composer.

VK-Y: Which is what a great performer does. Is that not right? The great performer meets the mind of a composer and does justice to the piece in whatever way the performer can.

KM: There are times when you can read something which is perfectly legitimate, and perfectly dignified, and perfectly scholarly, and perfectly thoughtful and not recognize all those qualities, depending on how it's expressed. I'm speaking of literature now. You could have something that is just said in a way that it has no appeal to you. Well, there are compositions like that also, and I think that Koussevitzky played music that had great appeal to him. He wouldn't play other things if they didn't have great appeal to him. He could grow into this appeal, but if he were not convinced of the worth of that music, I don't think he would play it. I think that's why he did Stravinsky so well. He was very impressed with the person that Stravinsky was. Similarly, he did great service to Bartók. That is because he had great respect and affection for the output of Bartók. I think Koussevitzky understood the complexity. He conquered those difficulties, and I think that there again Burgin was a great help. Burgin rehearsed the orchestra very well and all those Bartók pieces. And I think that Koussevitzky benefited from those productive rehearsals. He loved Bartók's creations.

VK-Y: When you mentioned earlier that something mattered to Koussevitzky, that brings up something that's concerned me for a long time. I feel in too many cases – and this is not just related to music but also to the visual arts, for example – that for too many people, whatever they're doing doesn't really profoundly matter. They're being musicians or artists, but what they're producing is not born of a deep inner necessity.

KM: It must be. It must be something that you're driven to do. You couldn't conceive of doing anything else at the moment you're doing it. Now, if you're an instrumentalist, you have to break through. The French have a wonderful phrase: "Il faut franchir les frontiers." You have to break through the wall, and I think that if you don't practice enough, you haven't broken through that extra thick wall that stands between the player's conception of the work as perceived by the composer and supported by the wisdom of tradition. You can bring so much to the table yourself that you don't see what the composer brought to the table. And that's a mistake.

VK-Y: And getting back also to Koussevitzky and his time, I just wonder what you feel about the fact that in many cases these were recordings that were being made for the first time of given works.

KM: That's true, very true.

VK-Y: I mean that he and other conductors of his era were going into a whole new world.

KM: The industry was in its infancy. He showed us the way, actually. He had such integrity – I can't imagine anything with greater integrity than, for example, those Tchaikovsky symphonies. The recording of the Schumann First Symphony – nobody had ever heard anything like it before. And that's what should be noted about Koussevitzky. People have never heard anything like his recordings. And I say that with all due respect to Furtwängler's recordings and to Toscanini's. There is something in the Koussevitzky recordings that was totally musical. You didn't think of the medium at all. It was just the greatest possible music-making, and I think those works that I was mentioning are just great examples for any conductor to follow, certainly the Daphnis and Chloé.

VK-Y: Yes.

KM: And the Francesca da Rimini – those were just great.

VK-Y: The live, March 11, 1944 Francesca da Rimini performance [a non-commercial recording – see Kevin P. Mostyn's June 2002 compilation of "non-commercial recordings known to exist," available on the Koussevitzky.com website] at New York's Hunter College is phenomenal.

KM: Those who heard them know that that's true. There might be people who are a bit blasé about these historical recordings. Possibly they have paid little attention to them, leaving their value undetected. Or they might be going merely on hearsay. Then they'll just agree with you, "Oh yes, yes, he was a great conductor," but they won't really have heard anything themselves. But once they've heard it, I think that they would agree that this is fine music making.

VK-Y: Well, there's also a Richard Strauss Death and Transfiguration – it's a bootleg performance and it is just, again, otherworldly.

KM: And the way he kept the pianissimo at the end.

VK-Y: Incredible performance.

KM: And he was able to keep the pianissimo better than any other conductor. That takes such discipline and patience to get everybody playing pianissimo for such a long stretch of time. It's an accomplishment for which I'm sure that Strauss would have just hugged him and said, "Oh, thank you very much!"

VK-Y: Yes. What other pieces would you say represent the apex of Koussevitzky's recordings or live performances?

KM: The fourth symphony of Beethoven, as well as the second, fourth, fifth, and sixth symphonies of Tchaikovsky – those five works for me just tell a whole story about Koussevitzky. The Mozart Jupiter, the other C Major, the 34th. It's been 40 years since I've heard it but I've never forgotten it. I'm sure that he recorded it.

VK-Y: According to Kevin Mostyn, there's a non-commercial recording of the 34th from July 20th, 1948, at Tanglewood.[2] And of course, and then there's Sibelius!

KM: Oh, the Sibelius Second. The Sibelius Second has never been done better.

VK-Y: Yes. You know, there are two performances – a 1935 recording, which is out on CD, and a 1950 one, which I do not think has been reissued. I prefer the 1950 version. Do you remember the two well enough to make a distinction between them?

KM: I don't. No. I'm sure I heard the earlier one.

VK-Y: I think that the later one holds together better. And the first one is certainly very beautiful and powerful, too.

KM: It was wonderful. I was very impressed with it.

VK-Y: He was magnificent with Sibelius.

KM: Oh good heavens, yes.

VK-Y: The Seventh Symphony with the BBC is just astonishing.

KM: I'm trying to think of any other work that just totally overwhelms me of the ones that I've been speaking about.

VK-Y: There's Debussy's La Mer and an extraordinary Brahms 3rd, of course. There's also a fabulous Schéhérazade.

KM: I'm sure there is, but I don't want to hear it.

VK-Y: You've heard the piece enough, I'm guessing.

KM: I've heard it enough. I was first cellist of the Hartford Symphony. That was my first job. We played that there. I played the solos in that, and I just felt if I hear it again, I won't be very polite. I was that way with the Rachmaninoff Third Piano Concerto, and I said to Natalie Hinderas that I felt that the piece was played too much and without real, what should I call it, in-depth thinking.

VK-Y: Well, I think it needs to be played by Rachmaninoff himself.

KM: By Rachmaninoff. I said this to Natalie who made her living playing Rachmaninoff, and I said that I'm not pejorating the composer. I'm talking about peoples' reasons for playing works. I think they try to show how loud and fast they can play the Third Concerto.

VK-Y: Right.

KM: And I think that in Schéhérazade conductors want to show how they can manipulate an orchestra. But I don't hear enough Rimsky-Korsakov in Schéhérazade except rarely, very rarely, and I do remember Koussevitzky doing Schéhérazade, and I loved it. I've rarely heard it where I enjoyed it from other conductors.

VK-Y: That's a splendid tribute to him again. Turning to various other questions, do you, as a cellist, have any comments on the Boston Symphony's string section?

KM: I don't know the string section now. But in the days of Koussevitzky it was the sonority from the string sections that was evident. I think that Stokowski got a wonderful sound from the strings in Philadelphia. Koussevitzky exacted a deep, more burnished one with the Boston Symphony. He himself got a gorgeous sound on the double bass. He had great virtuosity. He knew what the instruments were capable of. He knew, and he demanded and he got it. I would say that the sounds of the string section were thanks to a number of individuals, including the man who sat next to Jean Bedetti.

Bedetti's stand partner was Zighera, a wonderful cellist as well. That was a great cello section. The violin section was magnificent. The viola section was magnificent. I think the string section was unbelievable. There was a bass player with a great career as a soloist. His name was Ludwig Juht. He came to New York when I was a student at New York University. He came to New York and played a double bass recital in Town Hall, and with him was a violinist from the Boston Symphony named Einar Hansen. They played the Bottesini duo for violin and double bass together. The orchestra had people like that who were outstanding soloists, and I feel that Koussevitzky's philosophy was that an orchestra is a group of chamber soloists playing together. It was a great chamber ensemble with everybody listening to everybody else. And that's what Koussevitzky told you to do. He said "Listen" to everybody. That was one of the tenets of Koussevitzky. He urged the players to listen.

VK-Y: How do you feel that Koussevitzky's virtuosity as a double bass player affected his conducting of string players and of the orchestra in general?

KM: I think it gave him license to make demands. He knew that he could make demands because he knew that they would be achievable. And I think it's great to have had him as a double bass player. The bass foundation of the orchestra was outstanding.

VK-Y: Did he treat his double bass players, cellists, violists and violinists in any special different ways than the other musicians?

KM: I would have to say no because of what he asked from the winds, the horns, the flutes, the oboes. I think he was very demanding on everybody, and, as an outstanding conductor with all that experience in Paris before he came, he had something of a French attitude when it came to the woodwinds. And the woodwinds got such a sound, such a cohesive sound, because even though he stayed in France a rather brief time, he was really making French music. And he was, I think, under the influence of the French woodwind players when it came to the yield he would ask for. In fact, he had a lot of French woodwind players in the orchestra. He just brought them with him from Europe. Therefore, he was assured of getting that sound he was looking for. I think that the string players, however, had great respect for him as a conductor. You're going to have grumblers, I suppose, and no greater grumbler than Bedetti, who nevertheless had great respect for Koussevitzky's abilities. And I think that Alfred Zighera in a sense kept Bedetti fairly calm. Bedetti did lead that section well. Bedetti would talk to them, would turn around and say things to them sometimes in a rather impatient way. I don't believe that Koussevitzky ever spoke to them like that – the way that Bedetti spoke to them.

VK-Y: What were Koussevitzky's special strengths and weaknesses, or limitations, as a conductor, beyond some strengths you have already addressed?

KM: I don't know. At my age, I didn't know he had any weaknesses. And so now, in retrospect, I could make something up, but I don't think that he had anything that I noticed as a weakness.

VK-Y: What composers and pieces do you feel he played best and least successfully and why? Now, we have already talked about some of the best.

KM: Well, I think he played Bach very well. The B minor flute suite, that's wonderful. He did that with such panache and such depth at the same time. I thought that was extraordinarily successful with all the players. Bedetti played the cello solo passages, and the first flute was the summa of all that you would require from that B minor suite. The entire suite was, I would say, a crowning achievement for Koussevitzky. And the Magnificat, I heard him do the Magnificat – this was in the hall. So Bach, I would definitely say, was his cup of tea – and Mozart and Beethoven. He did the 88th Symphony of Haydn really well. And then Mozart, and I hope you can hear the 34th. They call it the little C Major because it's not the Jupiter. Both C Major symphonies are outstanding as rendered by Koussevitzky.

VK-Y: Do you have any comment on Koussevitzky's technique and how he managed to elicit such glorious playing from his orchestra?

KM: I think it's in the hands and in the face. He looked at people. He looked you in the eye when he was conducting. He would look to the first oboe. He would look to the horn. He would look to his principal string players, and he would get something from them – some connection from them. He would manage to connect with their minds and their sense of responsibility. I think it's largely that. I think that Zubin Mehta would always say to somebody, "You know, I can't see you. I can't see your face." And I understand what he meant. He wanted to have eye contact with everybody. And Koussevitzky could have been the source of that because he always had eye contact with everybody. Mehta had that same demand, that he could have eye contact with everybody. Koussevitzky, I think, might have been the person who started that. You certainly couldn't say that von Karajan had it because he kept his eyes down all the time.

VK-Y: Well, that's interesting. What about Stokowski?

KM: Stokowski had total contact with everybody. I think Stokowski is underrated because of his Hollywood trappings.

VK-Y: I agree. I think he was a magnificent conductor.

KM: He was a magnificent conductor.

VK-Y: And, for example, he managed to get such extraordinary tonal color from the NBC whereas Toscanini made it sound dry as dust. Suddenly the NBC had this glorious color when Stokowski was at their helm.

KM: Very few conductors have attained the level that Stokowski did.

VK-Y: How many African-Americans were in Koussevitzky's orchestra? Were you the first, and when was the next?

|

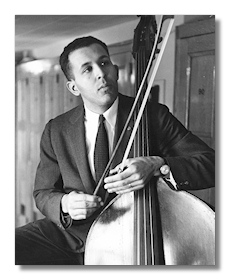

Ortiz WaltonPhoto courtesy Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives |

KM: I was a soloist, but I was never a member of the Boston Symphony. There were no African-Americans there when I played with them. Later Ortiz Walton joined – at a very young age.

VK-Y: Now what about the student orchestra?

KM: In Koussevitzky's student orchestra at Tanglewood, there were a number of African-Americans whom I still – well, those who are still with us – I remember. There was an oboist named Harry Smyles. Harry Smyles became one of the founders of the Symphony of the New World with me and with a few others. He was the first personnel director of the Symphony of the New World here in New York, and he was the first oboe.

We had a woman named Penelope Johnson, a wonderful violinist, who was a Juilliard graduate who played the Brahms Double Concerto with an older cellist named Marion Cumbo. Well, we're all older now but he was already elderly. A splendid artist.

VK-Y: Now were these African-Americans?

KM: African-Americans, yes. Yes, Marion Cumbo was a cellist who was one of the first graduates of the Institute of Musical Arts, which later became the Juilliard. And he was a pupil of a wonderful Dutch cellist named Willem Willeke. Willeke was the cellist who also taught the recently deceased Harvey Shapiro, who was the first principal cellist of the Radio City Music Hall Orchestra in 1932. He later joined the Juilliard faculty.

VK-Y: That's about the time when my late Mother – a Michel Fokine protégée, who was also a playwright and was trained as a concert pianist – would have been dancing as a principal member of the corps de ballet at Radio City.[3]

KM: My main teacher at the Cleveland Institute of Music, Charles MacBride – of Scottish origin – was a pupil of Willeke. He was the man on the first stand of the orchestra sitting with Leonard Rose. He was also a pupil of Willeke at the Institute of Musical Arts.

We also had a great singer who was very prominent at the time.

VK-Y: Was this an African-American?

KM: Yes – it was Adele Addison, whom you probably have heard of. She had a wonderful career. She has a vocal studio here in New York. She has taught many, many prominent singers. Another African-American was the recently deceased Arthur Thompson. He was a wonderful baritone from the Met. He did all of his vocal study with Adele Addison. But when I was at Tanglewood in the late '40s, she was a student there with the rest of us. She had a great voice. Subsequently she sang the Carmina Burana the world over. As an aside – and as a tribute to someone very special in my life – I want to say that my teacher at Juilliard was Felix Salmond and that I was his only black pupil. Felix Salmond came from England in the '20s. He gave the premiere performance of the Elgar concerto and the Schelomo of Ernest Bloch. These premieres were in England and in the United States. Felix Salmond was the cellist who came into prominence after the departure of Willem Willeke, and Felix Salmond taught Leonard Rose and Samuel Mayes – who happened to be of Native American origin – at the Curtis Institute. Salmond taught other cellists at the Juilliard. He taught many cellists. He was a wonderful cellist, and he was so thoughtful that he loaned me his Gofriller cello to play my Town Hall debut recital. I thought that was about as magnanimous as a person could be. He was a powerful personality who didn't have much good to say to you except that you were just not ready. You were just not prepared. You were just not satisfying his demands. He was one of the most demanding people, and he could utter his criticisms in such an acerbic way that you just had a tendency to want to go home and stay and not come out again. But he was so thorough as a teacher that you couldn't help but benefit from what he was doing and what he was saying.

VK-Y: Well, that's a tribute to him. As far as the Boston Symphony is concerned, when did they start hiring African-Americans?

KM: Well, when I was teaching at the University of Hartford, at the Hartt School – that was my first job by the way. It was 1950, when I was twenty. I got a job teaching at the University of Hartford, and I was in graduate school at NYU, and I taught cello and played in the string quartet in residence. The string quartet in residence was called the Hartt String Quartet. At any rate, there was a bass player who was a pupil of mine, in one of my classes. He was my age, but I was only twenty, and he was, too, but he was in one of my theory classes. His name was Ortiz Walton – he auditioned for the Boston Symphony and made it immediately. Now, here's what Ortiz did. He played the Mendelssohn Violin Concerto on the double bass.

VK-Y: On the double bass?

KM: On the double bass – all three movements.

VK-Y: Well, you know, this brings up something on the side: when I was, as an undergraduate student, the curator of the Mares Classical Music Collection at Williams College in the early 1960's, I bought a rare LP – for $35 – with Koussevitzky playing double bass and was astonished how he sometimes made the double bass sound like a cello, and also sometimes almost like a violin.

KM: Oh, yes, he did.

|

Ortiz WaltonPhoto courtesy Boston Symphony Orchestra Archives |

VK-Y: It was incredible. But returning to Walton…

KM: He was African-American. He got into the Boston Symphony in 1954.

It might have been '53. He took the audition, and they couldn't get over what they heard, so they hired him right away.

VK-Y: A larger question here is did Koussevitzky treat certain minorities or people of certain ethnic backgrounds differently from other orchestra members, or was he race-, color-, and ethnicity-blind?

KM: Well, there were no African-Americans in the orchestra when I knew Koussevitzky. He treated me with such kindness that I can't say anything critical of him. He was very thoughtful and very helpful. He wrote a letter to my parents telling them what he thought of me. And so I was just very, very not only touched, but I benefited from his thoughtfulness in many ways, because he found places for me to play, and I thought that was just outstanding.

VK-Y: That is wonderful. So as far as you know, then, Koussevitzky didn't have any prejudices of any kind towards any group of people? Would that be a safe statement?

KM: I would say no he didn't. I thought he was a rather forward thinker. I think some people would have called him progressive. I believe they were using the term progressive in those days. I think they were calling him progressive. Politically, I didn't find out that much about his attitude toward the Soviet Union because he never mentioned it. So I just didn't know. Now, as I said, I didn't have that many private conversations with him, but when I heard him talking with other people, I would hear him mention Europe – and certainly a number of artists from the Soviet Union – but I didn't hear him say anything political, either for or against the Soviet Union. So, all I know is from hearsay that he was a little bit or considerably embittered by his family's experience toward the beginning of the Soviet Union. I can understand that because that was a different world for them.

He did not grow up in that attitude, in that atmosphere, in that environment, and he probably felt betrayed by the government. He certainly left it, so he must have had a reason for leaving it.

VK-Y: Right. Was there any special way that he auditioned players, especially string players, and what qualities did he seem to want and want most in his players, specifically his string players?

KM: Well, he certainly wanted you to have dexterity. He looked for accuracy and dexterity and a beautiful sound. He would always say. "Make the most beautiful sound. Make the most beautiful sound. Put the bow in the string," things like that. That was a demand of his, and he would always get it. He knew how to get it. And I think that his auditioning was probably influenced by Burgin as well. He had a very strong influence over Koussevitzky.

VK-Y: How would you rate Koussevitzky among 20th-century conductors and among the Boston Symphony's conductors?

KM: Well, as I say, I know no other conductors that have reached the level of Koussevitzky and von Karajan, so anybody else is on a different level.

VK-Y: Would you then exclude Furtwängler from that group?

KM: Well, I didn't have any experience with Furtwängler.

VK-Y: Oh you didn't?

KM: I never heard him in person. I have a Beethoven Fourth that he conducted. I have a Beethoven Seventh that he conducted, a First and the Second. They're wonderful, but I wouldn't be able to pass judgment because the recordings were not very well made. I think that they were in the infancy of the industry – a lot was left to be desired.

VK-Y: Right. Just as an aside – because we were talking about the Beethoven Ninth earlier – have you ever heard Furtwängler with the Bayreuth Festival Orchestra and Chorus, with Schwarzkopf, Höngen, Hopf and Edelmann? I first came across that extraordinary interpretation in college, and it has since then been my favorite performance of the piece – and the LP is more powerful, rich, and subtle, I feel, than the more easily available CD version. Do you know that performance?

KM: I have that. I agree with you. It's unforgettable – wonderful, marvelous.

VK-Y: In terms of ranking Koussevitzky's versus other Boston Symphony conductors, would you want to make any comments?

KM: Well, I very much liked Charles Munch. I thought that he was a very expressive conductor who had a lot of discipline, tremendous discipline. I think that he had an easier time of getting through to the orchestra probably than Koussevitzky did because Munch, in a way, left them on their own. This is what I understand from various players – I used to talk with Robert Carroll, the cousin of Norman Carroll, who became a concertmaster of the Philadelphia Orchestra. Robert Carroll became a very prominent member of the viola section of the Boston Symphony, and we often played chamber music together and we talked about the orchestra. He says that Munch was able to have them eating out of his hand. He just had no problem reaching everybody, getting real results. I think that we take Munch for granted, and it's probably taken for granted that he was no Koussevitzky. I think that people had that view because Koussevitzky had such star quality. I don't think that Munch had that star quality. He had a scholarly quality.

VK-Y: He was marvelous with French music, for instance.

KM: Oh, he was outstanding.

VK-Y: I wanted to ask you about your judging of the Olga Koussevitzky competition – whether you have any comment about that judging and about the Koussevitzky competition in general.

KM: It was a very good competition produced by the Koussevitzky Foundation, and we have had some great talents. Some of our winners are concertizing very, very avidly right now, and one became the first violist of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. It was so long ago now that he's left it. I think that was about ten years ago. He became the principal violist of the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra. We've had cellists who have been outstanding and violinists. We had a poor crop of violinists the last time, but basically we've had some wonderful violinists. We have a competition also for voice, one year, winds, another year, strings, another year, piano another year, and the Koussevitzky recording prize is for compositions that are recorded within a given year by an American composer. So we have a lot of diversity in the instruments and in the disciplines that we are looking at. I think that it's a very good competition. We have had some good judges as well. I started judging for them in 1973. I became a member of the New York Musicians Club, and we had wonderful contacts with Mrs. Koussevitzky then, and that was just wonderful. She was a quiet person with such grace and dignity that nobody would ever speak loudly in her presence. People yielded to her and kept quiet so they could hear what she was saying. She was wonderful, I thought.

VK-Y: Well, that's beautiful. And how many times have you judged that competition, would you say?

KM: Eight or nine, probably.

VK-Y: Then let me go to another question here. Since both you and Koussevitzky have been champions of contemporary American music, did he in any way inspire or influence you in this respect, and do you have any comment on his support of American composers?

KM: When he was being – what shall I call it – responsive to American composers, he had Samuel Barber, and he had Menotti, and he had Roy Harris. We don't have any composers like that. So he could say, "Oh, I like this little tune here, this Knoxville 1915," that's a nice little piece, let's do that, you know, because Barber gave us so much, and before Koussevitzky died, he must have known everything that Barber wrote. He probably also knew Barber's teacher, Rosario Scalero, and had, for example, Walter Piston and Roger Sessions – those were outstanding composers. I think that now we have people who are afraid to be composers. What we have now are people who get themselves in a box, and then they make the additional limiting mistake of composing on the computer. And that limits a person to his ability to play keyboards. And if you play the keyboard, you are locked into the expanse of keys in front of you unless you are a great virtuoso on the piano, and then you become a piano composer and we've already had those. I think one was named Chopin – you can't do better than that. So I just wish the composers would leave the computer in its box, buy some music paper and put some indications on the paper in order to construct their works. Do you know that I have had, over the years, a supply house for my manuscript paper and for my pencils and everything? They had to go out of business because the mill that supplied them went out of business.

And so what I get now is the reproduction of all paper that I have had over the years and months, because it's now such a big industry to compose with the Finale or Sibelius systems of notation causing everything to sound sterile and and look sterile, and I think we've got to do something about it. We've got to turn the corner. We don't have the composers coming up with the kinds of music that Koussevitzky was accustomed to. I think that we have a wonderful composer named John Corigliano. He is a rara avis. Aaron Copland was championed by Koussevitzky. It's as if it's a different world. Think of what Copland has written – especially his later works – how he actually grew from the pieces that Koussevitzky knew.

The ballets, the boleros, the El Salon Mexico – those things Koussevitzky knew. He knew the Appalachian Spring, which is a great work in both versions, the small version and the large version. So Koussevitzky certainly is going to back music like that. I think probably what he would say today is, "Go home and write some real music," to these current people – I mean because he couldn't possibly like it.

VK-Y: I agree with you. I think the same thing's happening in the art world and the visual arts too.

KM: I bet it is.

VK-Y: Do you have any comments on the current state of music and culture in general in America?

KM: I think it has become too much influenced by sports and Broadway – we're on such a star system that we don't have the depth that we're accustomed to.

VK-Y: I agree.

KM: Everything has to be done with a twist of the hips or some outfit that is outlandish or some show that brings in a comedian or some work that is not really a classical work. We're getting away from what is really classical. Now, I'm not trying to sound like an old fuddy-duddy, I'm simply saying that if we don't show the discipline of the tradition – there is a discipline that the tradition dictates – and if we don't adhere to it, we're not going to have any classical music.

|

| Dorothy Rudd Moore Composer, Soprano Photo courtesy Kermit Moore |

VK-Y: Now let us go to you and your wife, Dorothy Rudd Moore. Could you discuss your and her work in supporting Black composers? Your wife is one of the most prominent women composers in America. Would you want to say something about her accomplishments and your close work with her, including commissions?

KM: The one thing we don't do is compose together. I have commissioned her to write two works, basically. One was the cello sonata called Dirge and Deliverance, which she did early on. That was in 1971. She wrote that for me, and I played it in my first recital in Alice Tully Hall. And she wrote an opera in 1985 called Frederick Douglass.

The other work that I commissioned was one that I really think is a landmark piece. It's called From the Dark Tower. She took eight poems by African-American poets, and she made a song cycle out of them. From the Dark Tower is a poem by Countee Cullen. So, she took that poem as the title of her piece, and that's one of the poems that she used. But there are eight wonderful poems by seven wonderful poets. I think she used two Langston Hughes poems. She used a Gwendolyn Brooks poem. Countee Cullen, of course, I mentioned. The work is very cohesive because she was able to make an entity out of the texts. It was premiered in Richmond, Virginia in a cello recital that I gave. The singer was Hilda Harris, who became a member of the Metropolitan Opera Company for some years, but she's retired. The work was orchestrated by Dorothy. We did it with the Symphony of the New World. It's been performed in many, many places. I conducted – if you'll believe it – the Birmingham Alabama Symphony in that work.

VK-Y: Isn't that interesting!

KM: And you wouldn't believe it. I was invited to come down and conduct. I said well, I'd like to do From the Dark Tower. They didn't know anything about what From the Dark Tower was, even though we had performed the work at Avery Fisher Hall. So they said, "Fine. It's a work by your wife? Huh, wonderful!" So I conducted it, and it's a powerful work and has such a message. It's not exactly the message that I would have thought that many people in Alabama would have wanted to hear. But it was very successful. They loved it. And I got the keys to the city as a result.

VK-Y: Oh, how fantastic! How beautiful!

KM: So if you want to go to Birmingham, if you get there late at night, you can borrow the keys from me. You can get in.

VK-Y: Thank you for the invitation!